About Gail Iris Rosslee

Let me introduce you to Gail Iris Rosslee.

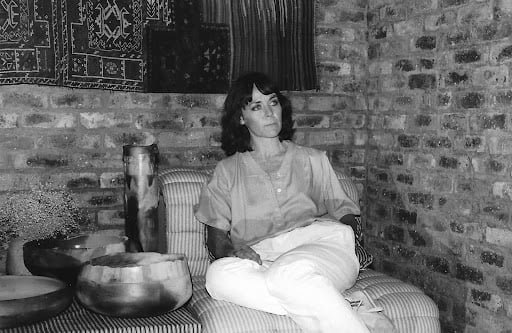

Now, is that the face of a sweet, compliant personality? Hardly. Note especially those clenched fists. She arrived as a whopping 5 ½ kilo baby straining a 5ft 2 mother.

She was a happy child, but she resisted, with disdain, over-affectionate uncles and aunts offering poached eggs.

In her early teens, her need for independence and freedom meant that her parents didn’t know much about her – how she and her best friend would cycle all-day distances, sleep out on Linksfield Ridge nature reserve near where they lived, walk home at night after movies. All risky South African activities.

A place in the National Ballet Company, PACT, was the consummation of ballet classes from a young age with highly regarded ballet teachers, Ivy Conmee and Majorie Sturman. But she chose Fine Arts over ballet during her 2nd year studying at Wits.

She didn’t work very hard at school or later at university. There were more interesting things to do. She joined political anti-apartheid protests along Jan Smuts Ave. She discovered jazz, Odeta, Bartok. On the weekends, she moved from one party to another. Philosophical discussions went on all night. She collected men and dumped them. She interrupted her studies to join a 50ft ketch sailing in the Med for two years. Again collecting declarations of love. She returned to complete her honours year.

And then, unexpectedly … she decided to marry (Neke). Her parents had to ask her who it was going to be. She had pushed this man away over and over but he was persistent. He was a nice man. But he didn’t excite her mind. And after a few years, and two children, she started what she thought was quite a friendly divorce. He had a nervous breakdown and didn’t pay maintenance. She ran a pottery and sculpture studio to support the family. She gained recognition in the field, lectured briefly, and won some awards.

Now, is that the face of a sweet, compliant personality? Hardly. Note especially those clenched fists. She arrived as a whopping 5 ½ kilo baby straining a 5ft 2 mother.

She was a happy child, but she resisted, with disdain, over-affectionate uncles and aunts offering poached eggs.

In her early teens, her need for independence and freedom meant that her parents didn’t know much about her – how she and her best friend would cycle all-day distances, sleep out on Linksfield Ridge nature reserve near where they lived, walk home at night after movies. All risky South African activities.

A place in the National Ballet Company, PACT, was the consummation of ballet classes from a young age with highly regarded ballet teachers, Ivy Conmee and Majorie Sturman. But she chose Fine Arts over ballet during her 2nd year studying at Wits.

She didn’t work very hard at school or later at university. There were more interesting things to do. She joined political anti-apartheid protests along Jan Smuts Ave. She discovered jazz, Odeta, Bartok. On the weekends, she moved from one party to another. Philosophical discussions went on all night. She collected men and dumped them. She interrupted her studies to join a 50ft ketch sailing in the Med for two years. Again collecting declarations of love. She returned to complete her honours year.

And then, unexpectedly … she decided to marry (Neke). Her parents had to ask her who it was going to be. She had pushed this man away over and over but he was persistent. He was a nice man. But he didn’t excite her mind. And after a few years, and two children, she started what she thought was quite a friendly divorce. He had a nervous breakdown and didn’t pay maintenance. She ran a pottery and sculpture studio to support the family. She gained recognition in the field, lectured briefly, and won some awards.

It was the early eighties. And politics had always played a major role in her life. A turning point for her came at the end of a company dinner. When everyone had moved off, she went up to the performing comedian and said: “Do you realise that while you are telling racist jokes, people are being killed in South Africa.” And then she punched him across the jaw. …

She decided she could not punch everyone. She had to use her anger positively. Her art became protest art. One of her sculptures, Eugene TerreBlanche and his Two Side-kicks, was bought by Isiko, at that time the South African National Gallery. TerreBlanche’s right-wing organisation, the AWB, found out about it. They called a regional meeting and the next day six hefty men in uniform, wielding hammers, went into the gallery and smashed it to pieces. The publicity was enormous. The gallery was quite pleased – it proved that art was not as irrelevant as everyone thought.

She decided she could not punch everyone. She had to use her anger positively. Her art became protest art. One of her sculptures, Eugene TerreBlanche and his Two Side-kicks, was bought by Isiko, at that time the South African National Gallery. TerreBlanche’s right-wing organisation, the AWB, found out about it. They called a regional meeting and the next day six hefty men in uniform, wielding hammers, went into the gallery and smashed it to pieces. The publicity was enormous. The gallery was quite pleased – it proved that art was not as irrelevant as everyone thought.

She also started working for the DPSC – with political detainees. She took statements, organised doctors and lawyers, photographed torture wounds, went into Soweto for meetings and returned schizophrenically to the apathetic white suburbs. Until Adriaan Vlok (Minister of Law and Order) decided to blow up the building where anti-apartheid organisations worked. And then in 1988, the DPSC was banned, together with all other UDF organisations.

So, she became the publicity secretary on the executive of another anti-apartheid organisation, the Five Freedoms Forum. The organisation was never banned, but the vice-chair, David Webster was assassinated, another member was shot at, phones were tapped. The security police and spies everywhere. The security police and spies everywhere. She moved her children out of the house.

In 1989, Gail was part-organiser and attendant at the largest conference ever held in Lusaka, Zambia, between the African National Congress, led by Oliver Tambo and Thabo Mbeki and white South African-based organisations.

In 1992, just before South Africa became a fully democratic government, she co-authored, with Frederick v. Zyl Slabbert and Michael Olivier, The South African Political Environment Survey, an extensively researched prediction of future political, economic, security, business and social trends plus the opinions of major political leaders and analysts.

More happened during these years. She fell in love, an exceptional relationship – now, in 2016, 36 years – choosing never to marry, of course. She put her two children through university; one to the level of Masters, the other to PhD. She also decided to go back to Wits in her late-forties to do a Masters degree herself. (MA Fine Arts (cum laude); Socio-Political Art in South Africa; University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.)

So, she became the publicity secretary on the executive of another anti-apartheid organisation, the Five Freedoms Forum. The organisation was never banned, but the vice-chair, David Webster was assassinated, another member was shot at, phones were tapped. The security police and spies everywhere. The security police and spies everywhere. She moved her children out of the house.

In 1989, Gail was part-organiser and attendant at the largest conference ever held in Lusaka, Zambia, between the African National Congress, led by Oliver Tambo and Thabo Mbeki and white South African-based organisations.

In 1992, just before South Africa became a fully democratic government, she co-authored, with Frederick v. Zyl Slabbert and Michael Olivier, The South African Political Environment Survey, an extensively researched prediction of future political, economic, security, business and social trends plus the opinions of major political leaders and analysts.

More happened during these years. She fell in love, an exceptional relationship – now, in 2016, 36 years – choosing never to marry, of course. She put her two children through university; one to the level of Masters, the other to PhD. She also decided to go back to Wits in her late-forties to do a Masters degree herself. (MA Fine Arts (cum laude); Socio-Political Art in South Africa; University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.)

Her art changed to another form of protest: looking at rape and violence against women and children in South Africa. Her research widened to exploring how men are taught by parents and society to enact their masculinity.

Her work was widely exhibited, in South Africa as well as internationally: Paris, San Francisco, New York, Mexico City, Osaka, Salzburg, Berlin and Birmingham. For six years, her hair was shaved to a number one.

She spoke on Masculinities at seminars and workshops held for institutions such as the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, National Association of Social Workers, Friends of the Johannesburg Gallery, and for groups of final year school students. She was guest speaker on Women’s Day at the SABC (the National TV and Radio Broadcaster).

She still intends to finish the book she is writing on the subject.

She found relief from the stress of researching this subject by writing a novel, The woman who Asked (available on Amazon).

Right now she is co-authoring her late father’s memoir. Her admiration for her pilot father makes this a personal pleasure.

Her work was widely exhibited, in South Africa as well as internationally: Paris, San Francisco, New York, Mexico City, Osaka, Salzburg, Berlin and Birmingham. For six years, her hair was shaved to a number one.

She spoke on Masculinities at seminars and workshops held for institutions such as the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, National Association of Social Workers, Friends of the Johannesburg Gallery, and for groups of final year school students. She was guest speaker on Women’s Day at the SABC (the National TV and Radio Broadcaster).

She still intends to finish the book she is writing on the subject.

She found relief from the stress of researching this subject by writing a novel, The woman who Asked (available on Amazon).

Right now she is co-authoring her late father’s memoir. Her admiration for her pilot father makes this a personal pleasure.

The next episode in her life is in the pipeline.